The ruins of Cojitambo located on a hillside in southcentral Ecuador

The Cañari people were a long-lasting independent pre-Columbian confederation of united tribes who formed a single people, and made up of fierce warriors that primarily occupied the Tumebamba area (present day Cuenca, originally Cañari settlement of Guapondelig), about 15 miles to the south and a little west of Cojitambo. It is interesting that the Cañari had an oral tradition of a massive flood as part of their creation stories, similar to those of the Bible.

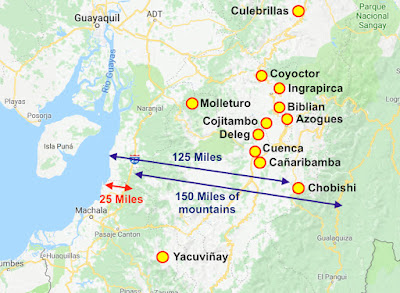

Map showing the area of the Cañari with (blue) arrows showing the

distances from the shore to the majority of sites; the second (blue) arrow

showing from the mountains in the west to those in the east; and the (red)

arrow showing the width of the narrow strip of land between the shore and the

beginning of the cordillera mountains. This entire area was inhabited by the

Cañari during Nephite times

It is believed that the Cañari came after the Tuncahuán phase (last century B.C.), a period archaeologists have not bothered to excavate and who know little about the people or their history and way of life. It is claimed the Tuncahuán culture flourished in the central highlands of Ecuador, and is believed to be traced back to 500 B.C. to 500 A.D.

Cañari ruins questionably assumed to date to the middle of the last

century B.C. in southern Ecuador

The name Cañari comes from “kan” meaning “snake,” and “ara” meaning Guacamaya: (macaw), suggesting these two animals were sacred to the ancient Cañari, who inhabited the southern highlands of Ecuador for more than 3000 years.

Some of the ruins of Cojitambo, situated on a high hill at the base of

the mountains

Ecuador is split by two cordilleras into coastal, Andean and Amazonian regions. The coastal region ranges from a tropical rain forest in the north to a mixed wet-dry monsoon region in the central and south. A third fairly low cordillera runs intermittently along the coastal strip. Among the volcanic mountains, known as the Corridor of the Volcanoes, lie rich, fertile valleys or basins, and at one time was centrally covered by lower mountains and hills—these were changed, many lowered into valleys, as the Andes mountains rose to great heights, altering the flow of rivers and the pathway of constructed roads through changing mountain passes.

The Cojitamba ruins are located 9,910 feet above sea level, less than four miles west of Azogues, having a strategic location with views of Cuenca, Biblián and Azogues, the latter being the capital of Cañar province. The site is considered to have been a military stronghold, and is named in Quechua (curi tambo) the “Resting Place of Gold,” though no gold has ever been found in the area. The site has 500-foot sheer walls of volcanic cliffs to the east and south of the ruins.

Far south of the Cañari lands is the area of Saraguro (today’s Loja, Ecuador), where much of the information on the entire district evolves, and is mostly about the Inca period when they instituted resettlement projects in the Loja area. Dennis E. Ogburn’s entire thesis and much of the scholar’s writings of Cojitambo surrounds these events of resettlement of a people that are known to have existed in the area from 500 A.D. to 1200 A.D., rising to the point of power between 1200 A.D. and 1460 A.D., when they finally fell to the Inca after an extended period of warfare in which the Cañari withstood the mighty warriors of the Inca for about ten years.

Map extended to include Loja, the Inca area of Saraguro

Now the problem lies in the citing of a 500 B.C. date for Cojitambo. This information stems from an obscure reference in some works that “Archaeologists have uncovered evidence that the site of Cojitambo was occupied from 500 BCE onward (Dennis Edward Ogburn, The Inca Occupation and Forced Resettlement in Saraguro, Ecuador, University of California Dissertation, Santa Barbara, 2001, p312).

However, in checking out this reference, there is no mention of a 500 B.C. date, but of a 500 A.D. date. In fact, the page referenced, 312, has nothing to do with any B.C. dates, and is mostly about the shape of the rocks upon which Cojitambo was built, and andesite stone the Incas quarried at Cojitambo and transported the blocks back to their northern capital of Tomebamba, as well as the “stones of Paquishapa,” the strategically-placed site of Villamarca as an administrative center for the Saraguro Basin, and that Tambo Blanco was an Inca site with local economic orientation.

In fact, in the entire 400-page work, Cojitambo is mentioned only twice, both on p312, and is regarding the site’s shape on the hill near Azogues that had “been likened to a sleeping lion and was an important sacred site of the Cañaris,” and was also the location of a fort.

Dates of the Cañari (Kañari)

civilization date from 500 A.D. (6th century) to 1533 A.D. when the

Spanish conquered the Inca and its satellite cultures

While we do not know the exact dates that Cojitambo was built and the Canari people occupied the area, we can be assured that it was sometime after the crucifixion and probably within the “golden years” of the Nephite Nation following the Lord’s advent and extended until the Nephites were forced into the north countries by the Lamanites during the final wars that ended at Cumorah. It is equally important to always keep in mind that dates used by anthropologists and archaeologists often fit into a pre-determined criteria, such as Ogburn’s “Preceramic,” “Early Formative,” ”Late Formative,” “Regional Development Period,” and “Integration Period.” Thus, circumstances are placed in dated categories that do not necessarily match their actual dated events.

As an example, the Cañari and Cojitambo have been dated to 500 A.D. to 1200 A.D., and later, so when a culture believed to have pre-dated the Cañari, who

The first to describe this Tuncahuán phase was the Ecuadorian historian, archaeologist and politician Jacinto Caamaño Jijón, whose investigation of five graves in a cemetery while surveying a pre-Hispanic settlement near the town of Manta, led to his discovery of the Tunacahuán. In central Ecuador, this phase or people were given a date of 500 B.C. to 500 A.D.; however, there has been very little archaeological research done in this region of Ecuador and both archaeologists and anthropologists “still have much to learn of its prehistory.” Yet, this lack of factual information does not stop the researchers from giving this rather unknown culture a date. It might be of interest that this so-called Tuncahuán culture has been identified through funerary items containing ceramic and copper—the very items used to describe the Cañari.

It might also be understood that researchers claim that “As there are no excavations on sites currently which were occupied during the Tuncahuán phase, archaeologists know little about the way of life of the people who produced these ceramics.”

Consequently, it seems reasonable to suggest that we look at such dates with caution, and not jump on unproven or even unresearched dating to determine when who and what is claimed to have existed in pre-historic times.

3 Nephi 8:12 - But behold, there was a more great and terrible destruction in the land northward; for behold, the whole face of the land was changed...

ReplyDeleteThis would seem to indicate that the narrow neck and land northward looked very different before and after the crucifixion. The "narrow neck" was such a defining feature of the landscape before, and it would have been considered a dramatic change to see it gone- no longer a neck of land bordered on both sides by seas.

The changes throughout the land were so dramatic that those survivors in the land of Bountiful could marvel at the changes even from their fixed vantage point after the darkness was lifted.

Very true. However, remember that Mormon wrote over 300 years after that event and had only the ancient records to tell him what it was like, and those may or may not have been very specific. From his viewpoint in 350 to 385 A.D., he was operating with a knowledge of a changed land of which he had no first hand knowledge of its previous appearance other than what he read in the records. So the changes we see in the scriptural record are obviously muted in the writing and fail to give us the real flavor of what took place--we only have a very limited set of comments in 3 Nephi.

ReplyDeleteTrue. That is easy to forget, that to the main writers, the post-cataclysm land was "normal." I think Mormon must have had a pretty good idea of how it was before, because he tried to give his readers a clear enough picture for the stories to make sense.

DeleteOn another note, here is a cool animation of the plate tectonic evolution of South America. The dating may be far off because it comes from a "no flood" perspective, but I like the look of the "Late Cretaceous" South America:

https://youtu.be/X0AqBCT8n4g

Also, I tried using your webform to send a question. I'm not sure it worked. It also doesn't have a way to attach photos. It was concerning the city of Nephihah.

ReplyDeleteYeah, I seem to spend all of my downtime reading the Book of Mormon, playing with Google Earth, and trying to read articles in Spanish these days. Thanks a lot, Del. My kids now think I'm a boring old man. I should probably go watch the new Star Wars to get back in touch with the modern world.

Hey Todd. Sounds like we have similar hobbies thanks to Del. I've created a google earth file that shows many of the possible Book of Mormon sites in the Andes. Thought you may enjoy it. Send me an email at david_kane6979@comcast.net and I'll send you the kmz file. I'd welcome your feedback.

DeleteYou pretty well described my life these days :)

ReplyDelete